Creighton Magid discusses the need for revisions to clarify the FTC’s Green Guides.

In a conversation with The Regulatory Review, Creighton Magid, partner-in-charge at Dorsey & Whitney’s Washington, D.C. office, draws on his experience litigating greenwashing claims to share his perspective on upcoming revisions to the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) “Green Guides.”

Greenwashing, the act of deceptively marketing products or funds as environmentally friendly, has become a topic of much discussion in recent years. A 2021 report claimed that 88 percent of Generation Z members say they do not trust companies’ environmental marketing claims. This skepticism, in part, led the FTC to announce plans to revise the Green Guides in 2022 and seek public comment on several key questions regarding standards for advertising products.

The Green Guides provide a tool for corporations to rely on when disclosing the environmental impact of their products to consumers. For example, the guides advise marketers against making broad, unqualified claims about the environmental benefits of a product.

According to Magid, revisions to the Green Guides are needed—in part to provide guidance to corporations when identifying their packaging as recyclable. Magid also stresses the importance of considering how revisions will affect product circularity—a system of resource use that minimizes waste in production and consumption.

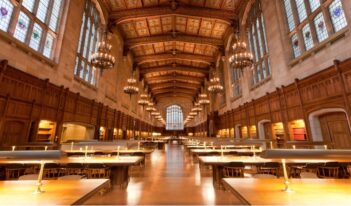

Magid has been a partner at Dorsey & Whitney for over 35 years, where he has defended multiple cases involving product liability and recyclability claims, such as Smith v. Keurig Green Mountain and Duchimaza v. Niagara Bottling. Since 2015, he has been recognized annually by Washington, D.C., Super Lawyers and Lexology Index for product liability. Magid serves on the board of the College Success Foundation and is a trustee of the Federal City Council. He earned his undergraduate degree from Princeton University and his law degree from the University of Michigan Law School.

The Regulatory Review is pleased to share the following interview with Creighton Magid.

TRR: How have the Green Guides been relevant in your work as an attorney? Given that the Green Guides are not binding law nationwide, how have you seen the Guides interact with federal and state law?

Magid: The Green Guides play a significant role in many of the consumer class action cases that I’ve defended.

Some states have incorporated the Green Guides into state law. The California Environmental Marketing Claims Act (EMCA), for example, essentially codifies the Green Guides.

At the same time, the EMCA provides a “safe harbor” that provides an absolute defense available when an environmental marketing claim conforms to the Green Guides standards or examples. In states that do not incorporate the Green Guides into state law, courts often view the Green Guides as persuasive.

TRR: Do the current Green Guides create liability or protect against liability for businesses that aim to market products as environmentally friendly? If so, how?

Magid: The Green Guides do both. For example, plaintiffs in cases involving claims of “recyclability” can cite the Green Guides to assert that a company’s claims are misleading because they lack a qualification, such as “may not be recyclable in your area.”

On the other hand, the Green Guides often serve as a defense. A good example is Duchimaza. In that case, the plaintiffs claimed that the caps and labels on certain plastic water bottles were not recyclable, rendering the claim “100% Recyclable” misleading. The court dismissed the complaint, noting that the Green Guides allow unqualified recyclability claims when “the entire product or package, excluding minor incidental components, is recyclable.”

TRR: The FTC originally announced plans to revise the Green Guides in 2022. They were last revised in 2012. Is there a continuing need for the Green Guides? Are revisions necessary?

Magid: There is an ongoing need for the Green Guides. The Guides provide a measure of certainty for companies in labeling and advertising their products. The large number of comments received in response to the FTC’s notice illustrate how important the Guides have become.

There are aspects of the Green Guides that merit revision or clarification. For example, recycling facilities may have the capability to sort and recycle a particular resin type but may elect not to do so from time to time if market demand for the material does not make recycling economically viable. May a product made of that resin properly be labeled as recyclable because it can be recycled, or would such a label be considered misleading because the resin is not currently being recycled?

TRR: Among possible changes to the Green Guides is an update to include guidance on the term “recyclable.” How do you anticipate that a more stringent standard, such as that suggested by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), will affect companies that market recyclable products? What about consumers seeking recyclable products?

Magid: It will be very interesting to see what the FTC does. The fact that it’s been nearly two years since the FTC announced its intention to update the Green Guides suggests that the FTC is wrestling with some difficult choices. It’s hard to predict what changes will be made to guidance concerning “recyclable” claims.

When soliciting comments, the FTC identified a central issue: “Should the Guides be revised to include guidance related to unqualified ‘recyclable’ claims for items collected by recycling programs for a substantial majority of consumers or communities but not ultimately recycled due to market demand, budgetary constraints, or other factors?”

If the revised Green Guides say that a “recyclable” claim is misleading unless a product is highly likely to be recycled in the existing recycling system, it will stifle efforts to increase recycling and build a circular economy: if there isn’t a “recyclable” claim on a product, consumers are likely to place the product in the trash.

On the other hand, if the FTC endorses “recyclable” claims based on the mere possibility that economics will favor collection and recycling of particular resins in the future, consumers could be led to believe that certain products will be recycled when the product almost certainly won’t be, absent seismic changes in end markets.

In its comments, EPA recommended limiting “recyclable” claims to products made of materials that have a “strong end market.” It’s difficult to reconcile that approach with EPA’s stated goal of “improving plastic product circularity,” since it would make it extremely difficult to expand the recycling infrastructure beyond what exists today.

TRR: The FTC also sought comment on whether it should impose mandatory rules about environmental claims through a rulemaking process, rather than through advisory guidelines. For businesses, what are the advantages or disadvantages of the mandatory rule approach?

Magid: Depending on how it is written, a mandatory rule could preempt claims arising from state law and could even limit consumer lawsuits by vesting enforcement authority solely in the FTC. The flip side is that businesses could face a rule that significantly limits environmental claims.

TRR: Are there any guiding principles that you believe the FTC should bear in mind when considering regulating environmental marketing claims?

Magid: The FTC should give very careful consideration to the effect that more stringent limitations on environmental claims would have on the ability of the United States to improve product circularity.